When I was 15 years old I was pretty clear about one thing. I was never going to be a mathematician.

I did not have a passion for numbers, equations were a struggle and pi was a complete mystery.

I was the kid at the back of the class with their perennial hand in the air every time the teacher asked if anyone had a question.

Maths was the anomaly on my report card. The thorn in an otherwise reasonably rosy garden. So in a bid to close the gap and prepare me for my GCSE my parents got me a maths tutor.

Sensible decision right?

Hour after hour over the course of the next few months I’d spend my extracurricular time trying to calculate the hypotenuse on triangles, condense algebra expressions and wrestle with simplified fractions.

To this day I still don’t know what any of that really means.

At the time my brain just didn’t want to compute it. I always came up with a different kind of logic, which rarely matched the one I was supposed to be using.

Try as I might, I just didn’t get it. This undoubtedly frustrated my tutor and it sure as hell frustrated me.

And the improvement could only be described as slight. The time and energy invested was not at all reflective of the outcome.

I was still a dunderhead when it came to rearranging formulas.

But here’s a question. What if instead of using my after-school hours to gen up on mathematics, I had spent them becoming more of a master at one of my top (and incidentally, favourite) subjects instead?

What would have happened if I’d channelled extra effort into English or Creative Arts?

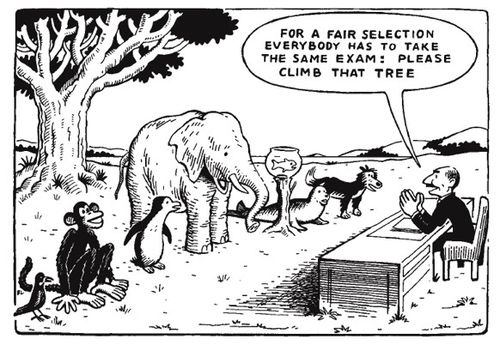

Oddly, convention focuses training and coaching on the areas where we lack natural ability, so we spend hours trying to fix our weaknesses rather than focusing on our strengths.

It’s an approach that’s often introduced by our education system and continued by our employers.

But it’s damage limitation at best and it’s unrewarding.

If you’re not a natural physicist or playwright, focused attention might mean you reach an average level of aptitude eventually, but you’re never going to be Werner Heisenberg or Arthur Miller.

Conversely, when you focus your energy on developing and applying your natural strengths and talents, you are much more likely to excel and find lasting satisfaction.

It’s a simple premise and one that feels great and pays dividends.

So whatever your own maths nemesis is, rather than over-commit development time and energy to it, try channelling your efforts into the things you’re already good at to develop master abilities.

You might just be amazed at the difference it makes, and your career trajectory will absolutely thank you for it.

P.S. If you’re interested in identifying your specific strengths and using this understanding to help direct your future career path, check out Work Wonderland.